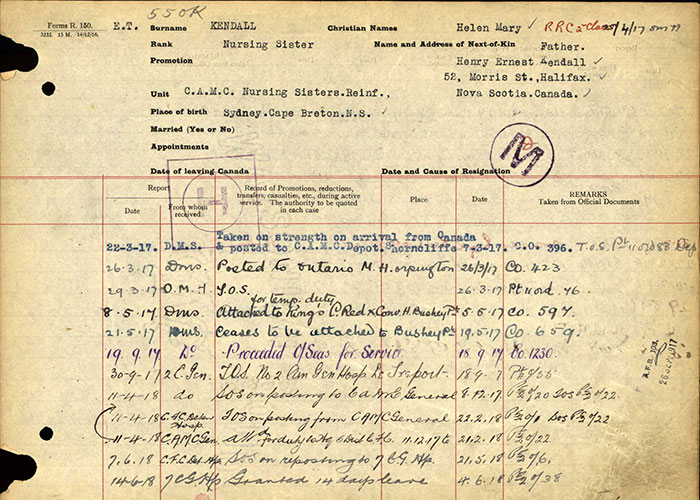

HK: Helen Kendall

I: Interviewer

HK: I hope that it’ll be worth listening to. I’m getting on. I’m 88 years old you know!

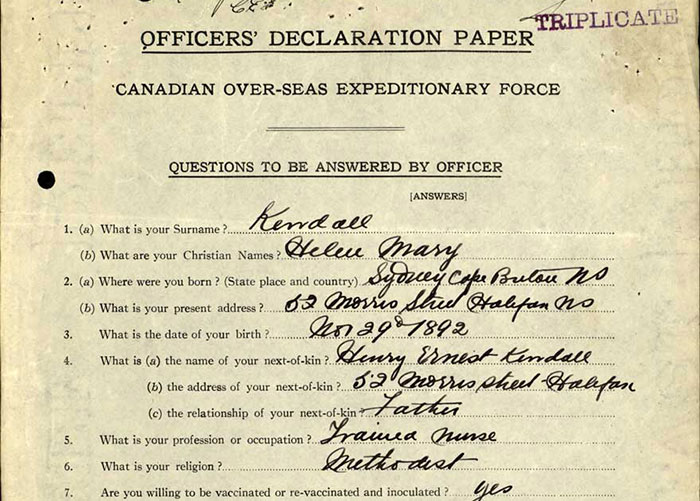

I: You were born and raised here in Cape Breton.

HK: In Sydney, oh absolutely. I’m a Sydney-ite, a Cape Bretoner, and I spent all my youthful life all around Cape Breton.

I: I want to know – why did you decide to train for a nurse? Why did you make that decision?

HK: Oh, I wanted to—I wanted to make some money, and be independent.

I: Do you remember why you chose to go over though?

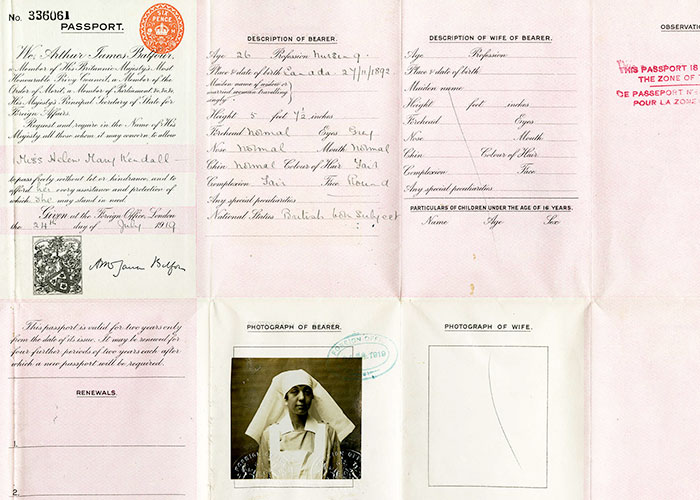

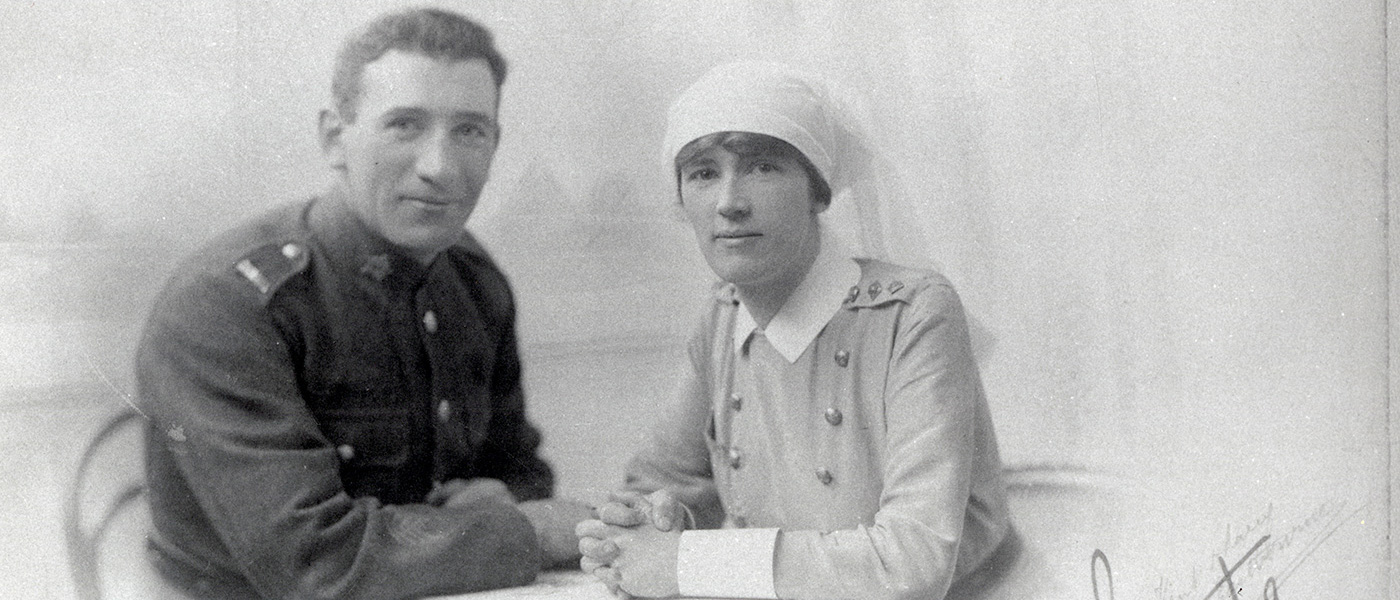

HK: Oh, well, there was a great deal – the whole communities here, we were close to the war, and all our men went off… we were just going over where our men were. We wanted to go over there and to see them and to help them. I was an anesthetist. I put people to sleep. Because I had trained in Montreal. I belonged to the Royal Victoria Hospital, and they gave me my education there, and then I was very handy because, when you went overseas, there weren’t doctors available to give anesthetics. The doctors were too busy looking after them, and operating on them, and were very glad to have people giving anesthetics. And we were well trained, and we were valuable.

I: Now you graduated in 1916 – I see your class was 1916...

HK: Yeah.

I: So you must have gone right over when you graduated because you were in France in 1917 I see here.

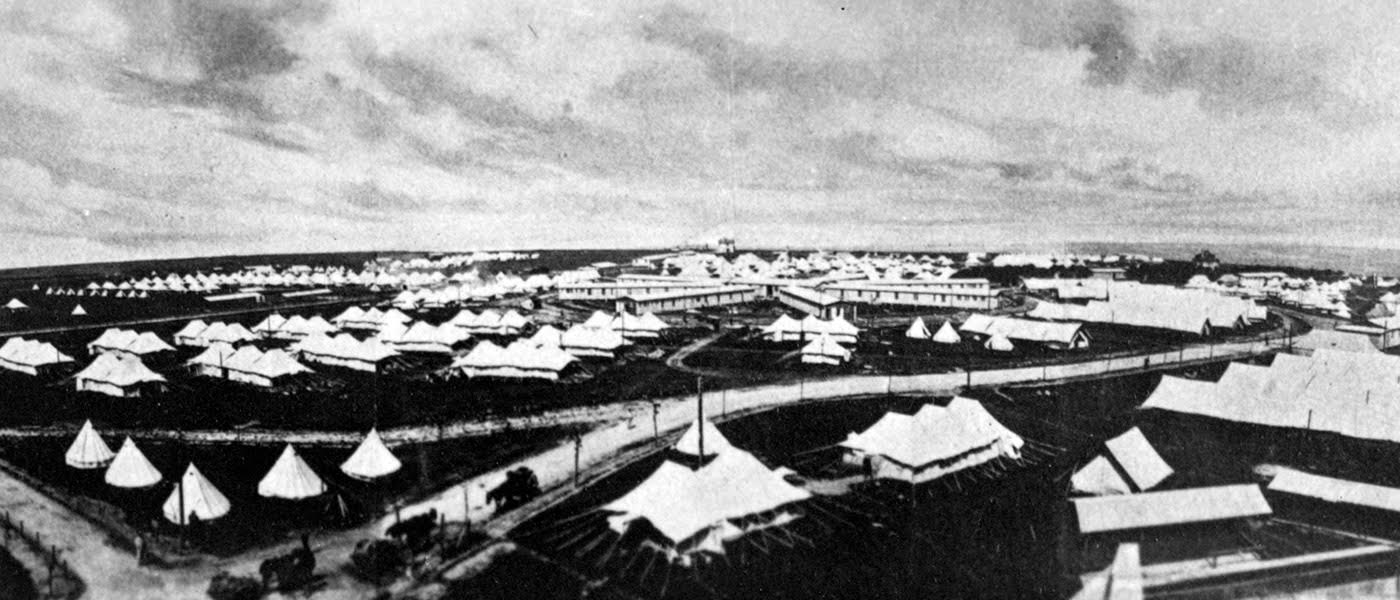

HK: Oh yes, we were in among it. We were right on the water. We looked across to England. The Canadians and the British built hospitals in France and then we went over and worked in them. The people who were fighting then were brought right down to our hospital, and we used to look after them. But they were the devil to give anesthetics to. They could fight like thieves! They were strong, and they weren’t going to be put upon, and we used to have two or three orderlies holding on to our patients while we were giving them the anesthetics to get them asleep.

I: I think it’s very exciting the work that you did during the war...

HK: Oh well of course it was, and we were lucky, lucky people to have that experience.